“When we all fall asleep, where do we go?”

Sleep. One of biology’s most perplexing mysteries that has left scientists scratching their heads for centuries. And even more puzzling are those elusive streams of mental processes called dreams that make us want to sleep for eternity lost in its depths or wake up in a heartbeat.

Historically, many have considered dreams to be divine heralds bringing messages of what is yet to come. Dreams have sown the seeds of inspiration for the work of different people across various professions and backgrounds, from singers like Billie Eilish whose album “When we all fall asleep, where do we go?” was inspired by lucid dreams, to scientists like August Kekulé who revealed the structure of benzene after having a dream of a snake eating its tail.

Dreams are one of mankind’s greatest mysteries and like the constellations that illuminate the night sky, they fill the dark, empty void of sleep and are simply begging to be explored.

“Sweet dreams (are made of these)”

Although a widely accepted definition of what is considered a dream is unavailable, dreams can be recognized as a mental experience that can be described during waking consciousness. The field responsible for the study of dreams is called Oneirology.

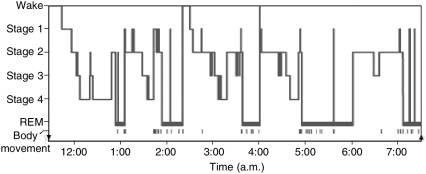

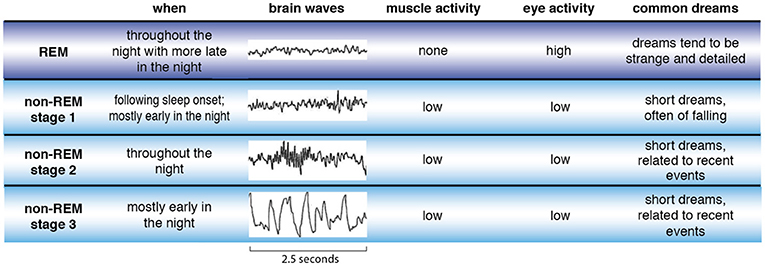

Dreams occur during sleep. Obviously. During sleep, humans will cycle through two distinct stages. One stage is called non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep and the other is called rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. NREM sleep is further divided into four subcategories namely Stages 1, 2, 3, and 4.

Each cycle can last for about 70 to 120 minutes and this time duration depends on the cycle of sleep, with later cycles generally taking longer.

Dreams can take place in any stage of sleep although they occur more frequently and with greater vividity during REM sleep. Dreams that occur during the REM stage tend to be more bizarre. REM sleep generally occurs towards the latter stages of sleep. REM sleep is characterized by the rapid eye movements that occur behind the closed eyelids accompanied by irregular and rapid heart rate and temporary paralysis of the muscles, preventing a person from acting out their dreams. It is considered that people spend roughly two hours each night dreaming.

The various patterns of brain waves emitted during the different stages of sleep can be identified by an electroencephalogram (EEG). The type of brain wave that dominates during REM sleep is called theta waves. Theta waves have shorter amplitudes and are the fastest type of brain waves.

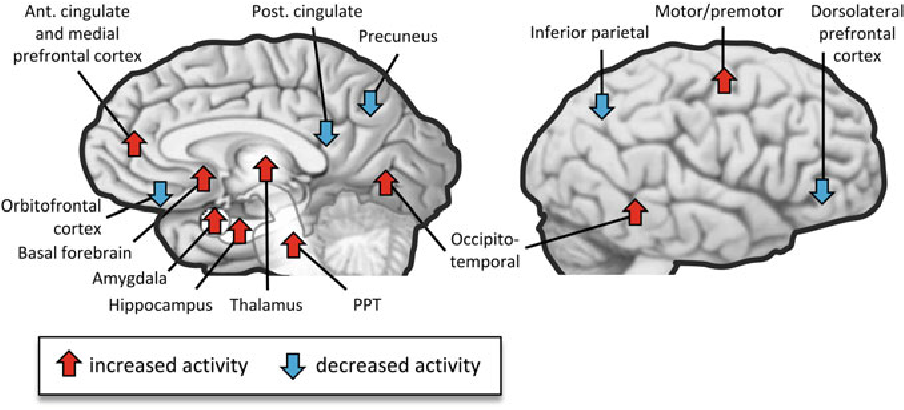

Different brain regions get activated during REM sleep and when we experience dreams. One of those is the amygdala, the part of the brain responsible for process and regulating emotions, typically fear and aggression which are quite common emotions experienced during dreaming. This suggests that dreams could have a possible therapeutic role, by helping us to process traumatic experiences in a relatively safe state of sleep.

Another region that gets activated is the hippocampus, which carries out the transfer of moving short-term memories to long-term. This has led scientists to theorize that dreams may help in consolidating our memories.

“The State of Dreaming”

The question as to why we dream may be as old as humanity itself. Many theories have been put forward to elucidate the cause of dreams. The study of dreams has been one of the most notable areas of interest of Sigmund Freud, author of The Interpretation of Dreams and the father of psychoanalysis. Although his views on dreams are debated, Freud theorized that dreams represent our unconscious desires and are generated due to wishful thinking.

Apart from Freud’s theories, many more scientists have introduced numerous theories to answer this question.

The Activation-Synthesis hypothesis: This theory – being one of the most prominent – proposes that dreams are the result of random firings of neurons and that dreams lack meaning.

Continual Activation Theory: This hypothesizes that dreams are formed due to our brains’ need to consolidate long-term memories. This is accomplished by a continuous data stream from the memory stores to the conscious part of the brain. This ensures that all parts of our working memory remain active during sleep.

Threat Simulation Theory: This provides us with an evolutionary function for dreams. As its name implies, the theory proposes that our dreams are our brain’s method of simulating threats and in doing so allow us to hone our fight-and-flight reactions.

The Defensive Activation theory: Introduced recently, puts forward a different answer to this pressing question. This theory postulates that dreams are our brain’s mechanism in keeping the visual cortex of the brain active during sleep. This is to prevent the other areas of the brain from taking over the visual cortex.

These are just a handful of the numerous theories that exist to provide us with the answers to why we dream and although it is unlikely that there is one specific reason, dreams are likely to serve multiple functions.

“Tell me all your dreams when you wake up”

Finding out what someone could be dreaming about may no longer be the stuff of science fiction. Although raising obvious ethical concerns, it is now possible to predict the content of an individual’s dreams with about 80% accuracy, with the use of machine learning models and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans. This remarkable feat was accomplished by a team of Japanese researchers, who conducted dream scans on three people over two hundred times. Brain scans can uncover much detail about the dream experience, including the emotions and actions and even the colors of objects in the dream.

“Guess I’ll just keep dreaming”

Ever had a dream where you were realized that you were experiencing a dream? Such a state of dreaming is called ‘Lucid dreaming.’ This state of dreaming – often very coveted – is a dream state where a person is aware that they are dreaming, and therefore, are able to exert some degree of control. Though exceedingly rare, lucid dreamers tend to be more creative and spend more time thinking imaginatively.

To the question of whether we can control what we see in our dreams, some researchers believe thinking about what you wish to see may contribute to incorporating it into your dreams.

“Life is but a dream”

There is a lot we still do not know about dreams and why they are formed. Although the amount of research on the study of dreams may be monumental, it has barely scratched the surface of what dreams are about, their causes, and their possible functions. But as science progresses, our understanding of dreams and the functions they serve will become clearer.

Dreams may just be the way our brains attempt to make sense of the endless random electrical noise generated during sleep. They probably serve more functions than one – or perhaps they don’t have any. Nevertheless, the science of dreams has much left to be explored and discovered. For the time being, our dreams, much like life itself, remains mostly a mystery and will, as always, never cease to fascinate and inspire the minds of many.

Written by: Yowan Dias

Image sources:

Featured Image: https://bit.ly/3lCE1R7

Figure 1: https://bit.ly/2Vl0ffY

Figure 2: https://bit.ly/37jdm3D

Figure 3: https://bit.ly/3jl11kW

References:

Cherry, K. (n.d.). Why do we dream? Retrieved July 28, 2021, from Verywellmind.com website: https://www.verywellmind.com/why-do-we-dream-top-dream-theories-2795931

Colten, H. R., Altevogt, B. M., & Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Sleep Medicine and Research. (2006). Sleep physiology. Washington, D.C., DC: National Academies Press.

Costandi, M. (2013, April 5). Brain scans decode dream content. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/science/neurophilosophy/2013/apr/05/brain-scans-decode-dream-content

Domhoff, G. W. (2003). The scientific study of dreams: Neural networks, cognitive development, and content analysis. Washington: American Psychological Association.

Eagleman, D. M., & Vaughn, D. A. (2020). The Defensive Activation theory: dreaming as a mechanism to prevent takeover of the visual cortex. doi:10.1101/2020.07.24.219089

Hobson, J. A. (2009). REM sleep and dreaming: towards a theory of protoconsciousness. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 10(11), 803–813.

Pagel, J. F., Blagrove, M., Levin, R., States, B., Stickgold, B., & White, S. (2001). Definitions of dream: A paradigm for comparing field descriptive specific studies of dream. Dreaming: Journal of the Association for the Study of Dreams, 11(4), 195–202.

Perogamvros, L., & Schwartz, S. (2015). Sleep and emotional functions. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences, 25, 411–431.

Stumbrys, T., & Daunytė, V. (2018). Visiting the land of dream muses: The relationship between lucid dreaming and creativity (p. 11588). p. 11588. doi:10.

Walker, M. (2018). Why we sleep: The new science of sleep and dreams. Harlow, England: Penguin Books.

Zadra, A., & Stickgold, R. (2021). When brains dream: Exploring the science and mystery of sleep. New York, NY: WW Norton.