We have been hearing a lot about ‘free speech’ recently – and not in the way that we in Sri Lanka are typically used to; not as a call to defend journalists and activists against persecution.

For example: the highly divisive Milo Yiannopoulos’ speaking appointment at the University of Berkeley was cancelled in January after students protested because he had, earlier last year at a University visit at Wisconsin, publicly outed a transgender student who was in the audience, by showing a picture of her before transition, as a ‘man’: naming her and all her friends, and framing her as someone dangerous and sociopathic. Protesting Berkeley students simply did not feel it was safe to invite this man on to their campus and give him a stage and hand him a mic. It wasn’t even about curtailing the spread of his particular ideology – it was about the literal and physical safety of students (especially already marginalised and at-risk students). The protesting students were actually standing up for ‘freedom of expression’ in a way – but we will get to this later.

Or to take an example from right here at home: a local online media platform decided to publish a piece on ‘Legalizing underage marriage’, written as a response to the struggle to reform Muslim Personal Laws in Sri Lanka; written by someone many of us know now to have a history of violence against women and girls. A Facebook post published in 2015 by a woman who declared this writer was her abuser when she was a young girl, alerted us to this reality – this man was now being given a soapbox from which to express his awful views about women (an earlier article he wrote was titled ‘Are women to blame for rape?’; his answer? Yes).

These persons are called ‘provocateurs’, ‘controversialists’ etc; we have come up with many words to disguise the fact that their deeds, words and ideas have very real, harmful effects on the lives of others and that they carry out these acts deliberately – not accidentally or innocently, not unknowingly – not merely to ‘spark discussion’. They are not interested in democratic debate and discourse. They are not interested in critically evaluating and evolving ideas.

The objectives of people like this are to harm, divide, ridicule, humiliate, and mostly, to express their own irrational and unfathomable anger and hatred towards others – to find ways to justify this irrational anger and hatred.

There are boundaries – there are boundaries that are not about us being unhappy when people express views in opposition to ours. It’s not about differing opinions. I think boundaries are crossed when people, through speech and expression, incite hate and violence towards others in a way which can have very real results – especially when we are speaking often of already marginalised ‘others’.

I think we need to talk about this. ‘Free speech’ is not a comfort zone. ‘Free speech’ is not a convenient argument by which to defend bigotry. Bigotry is not an ‘opinion’ which needs to be heard and examined and debated and discussed.

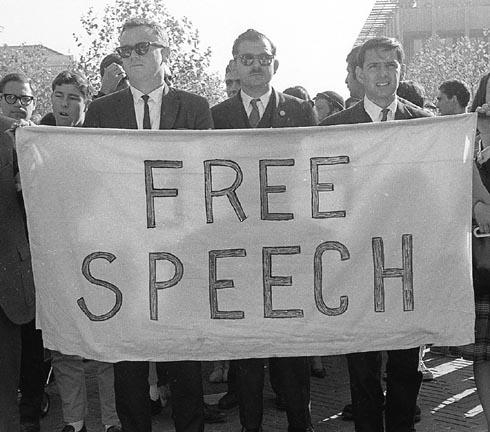

‘Free speech’ is a radical act. It is an act of dissent; it is an act of liberation in the face of oppression.

Free Speech, historically

Let’s understand ‘free speech’ a bit. The principles of free speech many of us subscribe to or think we know anything about are specific – not ahistorical. They are mostly shaped from Western philosophies and arose in Western history.

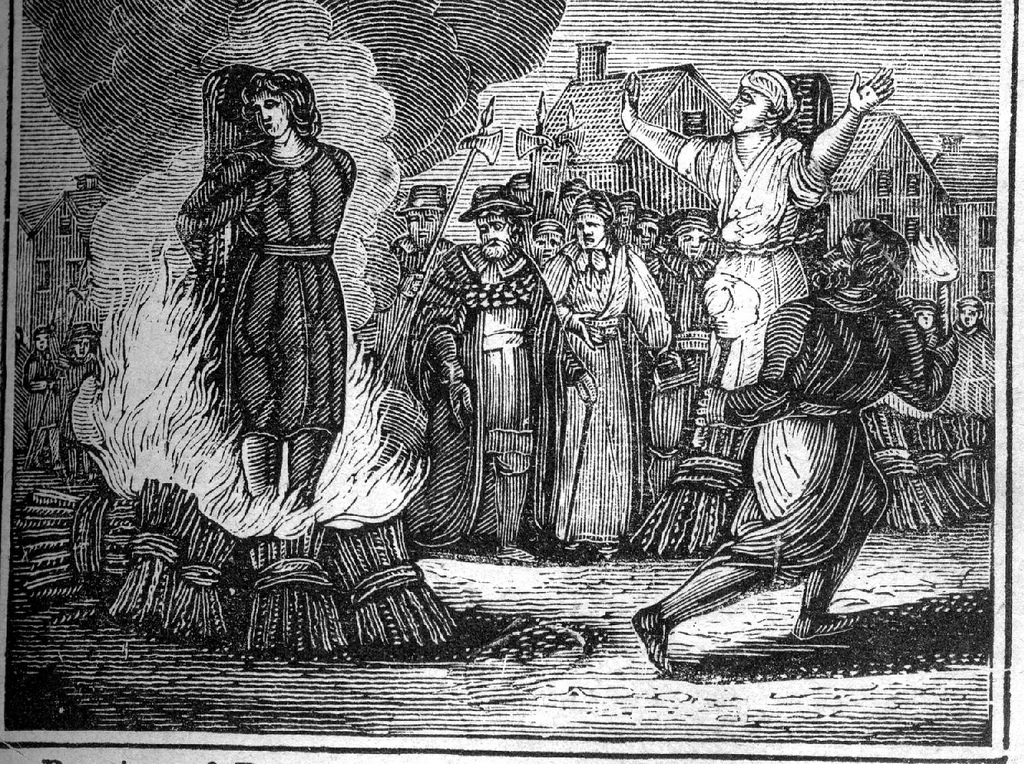

The debates around freedom of speech arose often in times of duress and institutionalised oppression; they arose in response to Church censorship – when the Church was labelling people ‘heretics’ and having them executed, for example. They arose in response to the state and Church working in concert, to control the very limits and boundaries of human knowledge-seeking and knowledge-production.

Today, it would be unthinkable to many of us to be censured or indeed killed for what we know, what we do – but don’t forget, this was common in Western history. Women (often women healers) who proved a threat to patriarchal establishments of power were burned at the stake as ‘witches’; scientists and thinkers who proved a threat to the Church’s stronghold on ‘truth’ were discredited and then killed. In later times, like in the McCarthy era in the United States, people were routinely, under suspicion and with no evidence, harassed and investigated on accusation of being a ‘communist’.

Much of Europe has a history of institutionalized, violent censorship – this is the world which then later assigned itself the role as protector of liberal values and freedoms, of which ‘free speech’ is paramount. However, as history tells us, ‘free speech’ itself was a conversation largely had among educated elites of the time, and this usually meant it was limited to men. Men like this gradually came to occupy positions as senators and legislators, and they turned the right to free speech into law.

This ‘free speech’ or ‘freedom of expression’, which much of Western history claims it fought and died (and killed) to protect, rarely if ever extended to persons or groups outside of this accepted mainstream – nor does it now, really.

It still doesn’t really extend to women (for example, women who express their sexuality openly are routinely still discredited and labelled ‘sluts’), it doesn’t extend to gender non-conforming queer folks, who by just being themselves and expressing their identities are considered a threat to society; it doesn’t extend to transpersons, when their identities can be erased simply by a denial of their identities; women activists or women identifying as ‘feminists’ are routinely discredited in public spheres, called ‘hysterical’, ‘angry’, ‘irrational’, ‘oversensitive’ or worse; it didn’t and doesn’t extend to systemically oppressed coloured or indigenous peoples who were enslaved and colonised – they are still expected to protest within the accepted norms of ‘protest’ sanctioned by white Liberal society: ‘Just protest peacefully, violence will undermine your cause’, ‘Oh don’t kneel during the national anthem, that’s so unpatriotic.’

So the West has a complicated relationship with ‘free speech’. The history of free speech is naturally as old as, and runs alongside, the history of censorship and both are a part of our reality at the same time; both also played and play a role in how our free speech rights are constructed.

But however we want to look at it, it’s clear that these rights have been important to humans since very early on. This concept is found in some of our earliest documents. And its importance clearly endures into the present day. All over the world, there are laws to protect the freedom of expression, the freedom of the press etc. Though today most of our laws about free speech or freedom of expression are fundamentally based on Western Liberal principles, and older classical principles borrowed from Greek theory, much of the world embraces these and makes them their own.

Free Speech and ‘The Truth’

BUT, even if we were to proceed with a very traditionally Western classical-Liberal argument about what constitutes the right to free speech, we would find something important. Simply, this is: ‘truth’.

Historically, many philosophical discourses about ‘the right to free speech’ seem to speak concurrently of ‘truth’. Whether you want to go the Cartesian way, the Milton way, the Foucault way (Parrhesia), you can’t escape the fact that ‘the right to free speech’ has more or less always been justified by the argument that somehow, somewhere, it is connected with ‘the truth’ and the truth is important to humankind. Now, we can debate about what ‘the truth’ is and what the construction of ‘truth’ is, but I am hoping we can all at least agree that ‘truth’ is important and fundamental to the act and right of ‘speech’ or expression (Susan H Williams offers one of my favorite explorations of the construction of ‘truth’ and free speech in her essay Feminist Theory and Freedom of Speech).

Foucalt’s observations on the Greek concept of Parrhesia defines it as ‘truth-telling’, where the Parrhesiastes necessarily has to be less powerful than the one s/he speaks against / about; Foucault particularly draws on the example of a ‘tyrant’ or a ‘king’ as the more powerful. It is always about revealing the truth in circumstances of risk and danger to oneself. Parrhesia is a noble act, a courageous act, and one taken by the Parrehsiastes at great personal risk.

‘Truth-tellers’ are persecuted still, in our societies, by those more powerful. In many of our countries, we are no strangers to journalists and activists being censored or detained by governments, for example, for speaking of state-sanctioned human rights abuses. We are no strangers to stories of people like Edward Snowden, who have had to flee their homes for safety because they dared to speak about government surveillance on civilians.

Look at what’s happening with impunity in the Maldives.

In Sri Lanka surely we need no reminder that not so long ago, journalists and activists who expressed dissent with any amount of visibility were at risk of being abducted or worse, killed. There is still a culture of military surveillance particularly in the North and North East of those who defy norms to speak the truth, or in this case, even remember and memorialize the truth. In circumstances like this, surely we should know better than to misuse the tenets of ‘free speech’?

When we rise to defend the right of ‘free speech’ are we always defending the people we believe with conviction are ‘truth-tellers’?

‘Free speech’ and the myth of censorship

‘In arguing against the proposition that free speech is threatened on college campuses, Yale Professor Jason Stanley declared, “Some cast today’s campus climate as a tension between antiracism and free speech. This is a false dichotomy.” He’s right. It is a false dichotomy…“We must consider the possibility that what is really happening,” Stanley said, “is that the language of free speech has been co-opted by dominant social groups, distorted to serve their interests, and used to silence the marginalized.”’ The Atlantic

‘Free speech’ is not about an act of the already-privileged asserting their dominance over others; it is not about defending hateful speech and not taking responsibility for causing harm to others. ‘Free speech’ is not about defending people who are reinforcing dominant repressive ideologies from which one would hope we have evolved. Real ‘free speech’ advocates are not the ones who only seem to bring it up when they’re trying to defend racism, or sexism.

Dominant repressive ideologies are not at risk of being censored. They are dominant. They are the most-heard. These are what are normalised and exist in the mainstream consciousness. To challenge these views as being outdated and unnecessary is not censorship; to ask ‘Are we simply reproducing already dominantly-existing, tired, old harmful norms?’ is not censorship. Questioning the amount of airtime repressive ideologies get is not an infringement on ‘free speech’.

We need to be wary of this false dichotomy: between ‘free speech’ and upholding other liberal, progressive values, because it invariably leads to divisions among generally liberal, progressive people. There is no contradiction between safeguarding equality and human dignity for all, and extending and protecting a true ‘freedom of expression’ right. These two things are in fact innately tied to each other and only possible together.

Freedom of expression can only be truly realized as a right when it extends to everyone. This is often not the case. When ‘free speech’ gets trotted out to defend the speech or actions of some which deliberately silence others, this is not ‘free speech’. ‘Free speech’ is especially not about silencing others.

Free speech and power

‘Speech’ isn’t literal and neither is ‘free speech’. There are many ways to silence others and to infringe others’ right to free expression; you can talk over them at a public meeting or in a public space. You can deny their expressed, lived reality (‘Oh surely sexism is not a thing anymore?’) or you can do so by discrediting them (‘You seem emotional, are you sure you’re being rational about this?’) or blatantly lying to contradict them (‘This is just something women make up’).

You can push your own ideology continuously as ‘the’ singular, objective truth, deliberately erasing dozens of other voices which have been saying otherwise (‘There’s no real problem with gender-based discrimination. Women are just over-sensitive’). You can erase people’s realities or identities (‘Were you born a man? OK, then I’ll just call you he’). You can bully or harass people into silence.

“The freedom to speak also includes the freedom for others to listen”, writes Catherine Sevcenko for FIRE, an American organization dedicated to defending student freedoms in colleges and universities.

But often, some people aren’t really listening; we are especially not good at listening to viewpoints which challenge assumptions we have taken for granted all our lives – especially about ourselves and our own positions of power. We’re often not proactively seeking out non-dominant narratives, questioning our own conditioning, thinking about how we use the rights and privileges of free speech and space to speak in; we’re not often reflecting on whether through our words and actions, we are also willfully shutting down the voices and truths of others.

We don’t really stop to reflect on how the ‘freedom of expression’ is innately connected to, and becomes a vehicle for, power: who speaks when; how frequently, and for how long? Observe: how loud someone speaks and the kind of words they can use and cannot use; have you been conditioned to have opinions, ask questions, seek knowledge, and further, to express yourself?

How do you frame your (how careful do you have to be vs how care-free or careless you are allowed to be)?

Culturally, does the society you live in accept you as a ‘knower?’ Someone who has opinions and someone who should express themselves? Are those expressions accepted, received? Are you allowed to express yourself however you wish – or are you expected to be polite, nice, make what you are saying palatable to the listener, even if it is something which challenges them?

Do you often find yourself carefully measuring what you are about to say, word by word, wondering what the responses might be to each word, aware that any word at any moment could trigger an assault against you – that your legitimacy could be questioned in a heartbeat? Do you find yourself constantly thinking about where that line lies – how far can you go before you have gone too far? Where can you stay that would still be ‘safe’ in how others perceive you but remain true to what you are saying and who are? Have you, say, ever been equated to a Nazi because what you’re saying fundamentally challenges systemic power?

And after all this careful consideration and the weighing of each word and each moment, do you still find yourself at risk of completely unprovoked attacks of a very personal nature?

Are you expected to stick by rules of communication which you never had any hand in making, and interestingly do not seem to apply to the people who did?

For some of us, speech and expression are never really free.

The original principles of ‘freedom of expression’ — however flawed and incomplete — were founded on the basis of protecting the disenfranchised from the powerful; on ensuring the less powerful also get a chance to speak; on guaranteeing their voices can be heard and their right to be heard, protected; on guaranteeing that the people with all the power and resources do not by default take up all the space. Dissenter vs state; ‘knower’ vs church. This was the idea. In fact, it was emphatically not about protecting the more-powerful from being challenged or criticized.

It was about upsetting established power, not reinforcing it.

Our rights are indivisible, that’s the point. Our rights aren’t separable; not individually and not collectively. Meaning, as individuals, the fulfillment of our rights are inter-linked; as larger communities, we can’t really consider it a fulfillment of our rights, if those manifestations of fulfillment directly violate the rights of others – that’s not a fulfillment of our ‘rights’. Those are just selfish entitlements and expressions of dominance and oppression.

Free speech will only really be free speech when it applies and extends equally to us all – and this requires the most rigorous self-interrogation from each of us; we have to also aspire to good speech, useful speech, noble speech and inclusive speech which opens, not closes, the debate.

Leave a comment