The Legend of These Roadside Boutiques AKA The Local Tea Shop

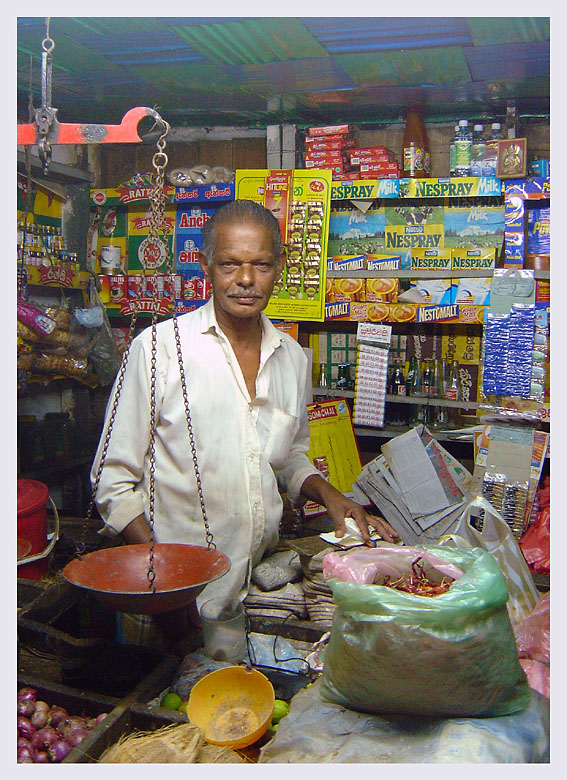

Kades, the traditional Sri Lankan shops or booths, sell an overwhelming variety of goods. Mostly gone from urban areas they are still common in rural areas.

If you happen to be travelling in Sri Lanka by road and require refreshment, desist from stopping at that modern establishment with its plastic tables and soft drinks. Rather, seek out a traditional kade (shop) with a simple wooden seat in front and a bunch of thambili (king coconut) lying inevitably beside it. With several deft cuts of a large knife (which look disconcertingly like a rusty machete) the thambili will be prepared for you to drink straight from the nut. It is more refreshing than any kind of mass produced aerated beverage. A cup of hot steaming plain or tea is also usually available, along with “short eats” – pastries and buns filled with spicy fish or vegetable concoctions.

The kade was formerly known as boutique (not from French origin but a corruption of the Portuguese word butica or boteca), has all but disappeared in Colombo and the other large Sri Lankan towns, although some examples are still found in rural areas. The most basic ones are constructed of wooden boarding with a window counter through which the proprietor conducts business. Bigger kades are built of brick but are open at the front in order to hang fruit, display rows of vegetables on trestles, and store sacks of rice, dhal and gram on the floor.

The proprietor of a kade is called a mudalali. Almost invariably he wears a banian (vest) and sarong. In earlier days he would wear a jacket over the banian and sport a konde (knot of long hair at the back of the head). The mudalali is one of the key persons in the village, because most of his customers, being poor and without cash for most of the month, have to rely on the credit he is prepared to give them. You won’t find any cash registers or other commercial paraphernalia in a typical kade, just a pair of scales and perhaps a pocket calculator.

Historical Literary References to Kades

That kades and other traditional mercantile establishments have changed little in the past 100 years is demonstrated by the following passage from Bella Woolf’s How to See Ceylon (1914): “The native shops – boutiques they are called in Ceylon, a relic of Portuguese days – are open to the winds of heaven. Here the seller sits cross-legged or on his haunches on the floor, while all the day and far into the night the purchasers swarm around. Strange to European eyes are the sacks and baskets full of curry stuffs, chillies, Maldive fish, and grains unknown to the West, kurakkan, gingelly, paddy and gram. The fruit shops brim with plantains (bananas to most people), pineapples, rambuttans (red and green round fruits covered with prickles), mangoes, custard apples, papaws, breadfruit, brinjals (purple and white), and pumpkins.”

“’Candles for sale’ is the device outside one boutique and attenuated specimens of the candle tribe dangle on strings. There are boutiques displaying gay-coloured clothes and hankerchiefs, there are betel leaves impaled on sticks, sold together with arecanut and lime for chewing purposes. In some places tailors are sewing for dear life – a tiresome touch of the West. In another doorway a woman sits at work on pillow lace. Here is a barber shaving his victim coram populo, or an astrologer casting a horoscope.”

In a further reference, Woolf writes of the boutiques peculiar to Jaffna (at the very northern tip of Sri Lanka): “Even the cadjan houses, it will be noticed, are built up against the fence and if they serve the purpose of boutiques as well as dwellings, the goods are not displayed for sale. The buyer pokes his head through a hole in the fence and calls out for what he wants.”

There are many other references to the humble boutique from English literature pertaining to Sri Lanka. For example, William Skeen relates in Adam’s Peak (1870): “We were overtaken by a smart shower, and gladly availed ourselves of the shelter of a boutique on the wayside.”

Henry W. Cave comments in The Ceylon Government Railway, also known as Ceylon along the Rail Track (1910): “Chatham Street is composed of a strange medley of restaurants, native jewellers, curiousity shops and provision boutiques.”

Clare Rettie remarks in Things Seen in Ceylon (1929): “The boutiques – or small shops – are piled high with vivid coloured cloths, all sorts of ingredients for curry making, betel for chewing, etc.”

- Brooke Elliot advises in The Real Ceylon (1938): “The village boutiques (shops) are worth quiet inspection, including the Toddy-Shop or village ‘Pub’”

While such scenes can still be witnessed in rural areas, the average Sri Lankan shop at the beginning of the 21st century is a more prosaic affair. Nevertheless, the colourful arrays of vegetables, and sacks of rice and other commodities will arrest visitors. Even displays of mundane items such as biscuit packets have a distinct dimension of their own. Furthermore, innovative methods are employed. Circular nappy-driers with dangling clips, for instance, are used to hang a variety of small items from crisp packets to sachets of detergent.

boutiques haven’t disappeared from Colombo at all. we just don’t notice them anymore. but head into any of the traditional middle class residential areas and you’ll see plenty of them.

I guess disappear was a strong word to use but they are dwindling in numbers. When I was still a smoker 2 years ago I remember finding it increasingly difficult to find a small kade to buy a packet of Goldleaf in Colombo. Admittedly I don’t venture into residential areas too much when I’m there. What do you mean by traditional middle class though? I would have thought the poorer residential areas would be more likely to have old style kades and residents from better off areas would be far more likely to pop into their neighbourhood Food City outlet for something small, hence causing the kades to go out of business.

well, places like Wellawatte, Dehiwela, and Mt Lavinia along the Galle Rd. then inland, Pamankade and Kirillapone, Nugegoda, Narahenpita, even Borella and outwards from there into Rajagiriya and Kotte. i recently went to northern Colombo, Kotahena and Mutwal, and you see lots of these little boutiques. what’s happened in the more posh places like Colpetty and Bambalapitiya they’ve retreated from the main roads, so you don’t see them unless you actually live in the area.

The ones on the Galle Road in Wellawatte, Dehiwela etc. are evolving though – some take the grocery shop route and others the bakery/milk bar/cool spot route and introduce tables, chairs and displays for food etc. I do know of some “old style” kades on the beaches at Dehiwela/Wellawatte though (I lived in Dehiwela for a while in 2006/2007) that mainly serve the fishing communities there but unfortunately some of these are quite dodgy!

even in those areas you’ve got to get off the Galle Road to find the real boutiques

Nice post. I wonder if Clare Rettie is related to late John Rettie the former BBC correspondent here?

Thanks. I have no idea – might be worth looking into. 🙂