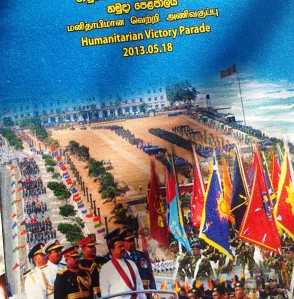

Invitation to a military parade taking place in Colombo, Sri Lanka, on 18th May 2013 marking the fourth anniversary since the defeat of the LTTE by the country’s security forces

“This development is not ours, they just come in and do as they please, and we stand by and watch”. “What are they complaining about so much? We won the war for them. They should be content with that”.

The first was something said to me by a prominent Tamil businessman in Trincomalee when, around the same time last year, I gave a round of calls to my friends in the biz community in the North and East districts to get their pulse on developments since May 2009. He was grateful for the end of the war and the fruits of commerce it brought with it, but was sad how much indigenous businesses, and communities at large, had been sidelined and marginalized in the post-war period.

The second statement was something said to me by a high-ranking Sinhalese local government official in Mannar, around the same time last year when I met him and inquired as to why people seem to feel “left out” of development activities. He said it in raw honesty, he meant it, he believed it, he seemed to be one of many who felt exactly the same. That was quite disconcerting.

These bring me to the point of today’s piece, marking four years since the military defeat of the LTTE, the release of thousands of civilians trapped in the final battleground, and the beginning of an arduous journey towards recovery and development. Two of the most critical challenges relating to post-war economic growth are 1) making people part of the progress, and 2) getting our spending priorities right.

Making People Part of the Progress

Insufficiently addressing the legitimate economic aspirations of the people, and making them part of the new rapid development, is a recipe for disaster. Not only is it unwise from a socio-political viewpoint as it fosters people’s discontent, but it is unwise from an economic standpoint too. If all people of a country aren’t able to fully contribute to that country’s growth, then the country will be growing at less than its potential. Quoting from Sri Lanka’s first publication that comprehensively looked at post-war inclusive growth:

Inclusive development, however, is not only about sharing growth. It is also about empowering people to participate meaningfully in creating growth. This involves empowering people through investing in their health and education and giving them equitable opportunities to access productive resources.

The businessman from Trinco should no longer be left to feel that “this new economic development is not his”. The government official should no longer be allowed to think that “people shouldn’t fuss about being included in the development, they should be thankful that the war ended”. Everywhere you go in the North and East, the majority are certainly thankful. But that doesn’t mean that this feeling will forever sideline their wishes to be part of progress. The longer a government thinks that, the more toxic the situation becomes.

The Asia Foundation’s Private-Public Dialogues (PPDs) initiative offers salutary lessons on how, at the local level, entrepreneurs and government officials can come together to address area of mutual concern on economic development issues and jointly develop, even in a small way, a collective development vision for the people of that local authority area. I witnessed how the Batticaloa Municipal Council and various producer groups in the town came together to develop their own tourism vision for the district. They acknowledged that the government has its broader plan, but they wanted their own – to determine the tourism trajectory for their hometown in a way that best serves them. That was unique and path-breaking.

One clear characteristic of Divineguma – the new gargantuan livelihood development programme – is that it will consolidate the the direction of development in Sri Lanka by the centre. The government’s thinking must be that, if it slowly loses control of all the Provincial Councils and the Local Authorities in the years to come, it still has the powerful and rich Divineguma development programme to give it substantial influence over people’s economic prosperity, from the center. What better way to keep a grip on the trajectory of an election?

Getting Our Spending Priorities Right

I type this as I watch the military parade taking place at Galle Face (only so I can count the number of new SinoTruk vehicles – more on this in a minute) and the six words that pop to mind are “expensive. can’t afford. better spent elsewhere.”. So the second challenge, most relevant to today, is finding the money for development in Sri Lanka.

As Sri Lanka moves well into lower middle-income status, we will get less and less concessionary foreign aid. Simultaneously, Sri Lanka is collecting less and less tax revenue (fell to a 20 year low of around 11% of GDP last year). Tax revenues are what economists call ‘domestic revenue mobilization’ – a critical ingredient in development. If a government doesn’t have the money, how will it finance development? Of course, it can keep borrowing (on commercial terms) from abroad, but this comes with a whole host of complications that Sri Lanka might not be geared to tackle fully. So at a time when budgets are tight, tax revenues are taking time to bounce back, the country must prioritize its spending. It is all a question of allocating scarce resources, at the end of the day right? Economics 101.

The country must ask itself, “can we afford that extra airport right now? Will the costs vs benefits weight out? Should we put it off a few years?”; “can we afford the lavish parades and May Day rallies on the tax payers account? When we aren’t raising as much revenue as before either?”; “should we not borrow from China for that next coal power plant, and instead come up with a clever PPP scheme and get the private sector to invest, but regulate it effectively?”; “could we have sold that prime state land in the middle of Colombo to a more reputed party who would have paid more for it, been more discerning, instead of to a relatively unknown, unsolicited one who came in through a connection? Doesn’t that hurt public interest, and in turn public finances?”; “do we need those twelve new trucks we see in this year’s parade, all purchased from the Chinese state agency SinoTruk? Why did we buy them, since we are no longer in war-time? Could this have been better spent on building clinics in Kilinochchi and schools in Buttala?”.

These are just a handful of the many questions to be asked, as we enter the fifth year since the end of the brutal conflict. All Sri Lankans fought hard for it. Some directly in the line of fire giving up their lives, while others put off ambitions and aspirations of economic prosperity, suffering high inflation and low growth, to ‘let the country defeat terrorism first’. All Sri Lankans must be part of the progress after its end. That’s just good economic sense. Leaving room for a “they vs. they” situation hurts Sri Lanka’s post-war economic prospects.