Sri Lanka’s ancient cities of Anuradhapura, Polonnaruwa, and Kandy form what most tourism brochures refer to as the Cultural Triangle. And rightfully so—five out of Sri Lanka’s six Cultural UNESCO World Heritage Sites (and one of two Natural sites) are found within these three corners.

Most visitors are drawn to these sites for the prospect of travelling back in time. Attractions such as Sigiriya also showcase how Sri Lanka was once ahead of the curve in terms of architecture and construction. But there is also a third factor that draws tourists: the spirit of adventure and the thrill of discovery. And that’s where an archaeological biosphere like Ritigala comes in.

A Strict Natural Reserve

Often overlooked by tourists, Ritigala is one of only three Strict Natural Reserves (SNR) found in Sri Lanka, making it a protected area dedicated to the survival of threatened species. In SNRs such as Ritigala, there is minimal human disturbance. Access to higher altitudes is reserved for scientific purposes and requires special permission from the Department of Wildlife Conservation.

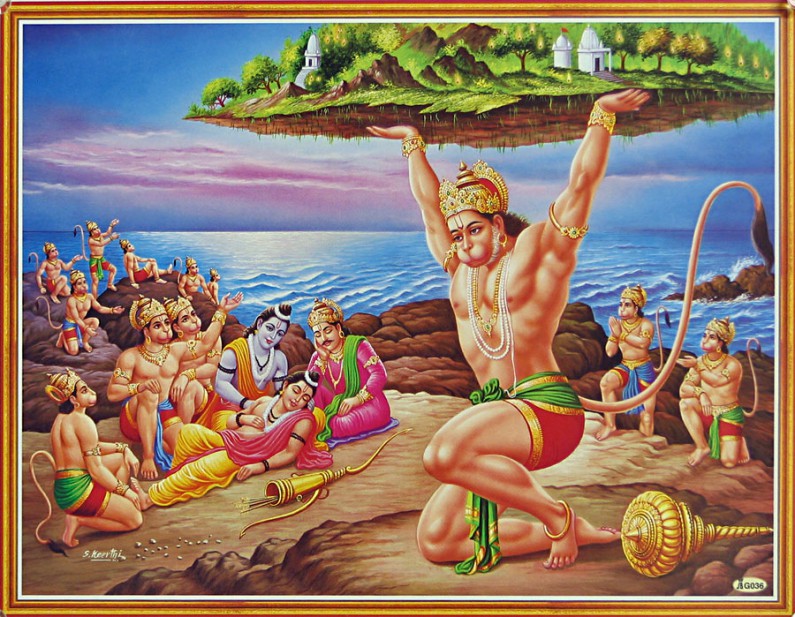

Special permission is required to access higher elevations of Ritigala. Image courtesy Harrogate Medical Wine Society

The fascinating ecosystem of Ritigala features mixed forests upon the slopes of a mountain range, which include an eponymous peak standing 766 metres high—the tallest mountain in Northern Sri Lanka. Its defining features include the microclimates that enable the growth of a diverse vegetation. This occurs because the foot of the Ritigala range shares a similar climate to that of the surrounding region: hot and dry, while its summit is the opposite: cold and wet.

In a study on lichens at Ritigala, the University of Sri Jayewardenepura identified microclimates by the change in light and moisture at different elevations. As a result, the study showed a variation of lichen species on the mountain, whose distribution and diversity were determined by the microclimate that they grew in.

Monastic Ruins

Ritigala is also known for its preservation of an ancient monastery similar to Arankale. Built by King Sena I in the 9th century AD, the monastic ruins came to light in 1893, when Ceylon’s first Archaeological Commissioner, H.C.P. Bell, made an extensive account of the area. Prior to Bell’s expedition, Ritigala remained untouched since the 11th century, when the monastery was abandoned due to invasions from the Chola Kingdom.

It was also during this time that Sri Lanka’s capital shifted from Anuradhapura to Polonnaruwa, thus causing its many resident monks, known as the Pansukulikas, to leave Ritigala. Meaning ‘rag robes’, Pansukulikas were ascetic priests who detached themselves from monks in Anuradhapura, and practised extreme austerity by taking a vow to wear robes made of abandoned rags gathered mostly from cemeteries.

The Banda Pokuna is said to have once held 2 million gallons of water. Image courtesy writer

Entering the ruins, the Archaeological Department Office sits close to the bund of the Banda Pokuna— a man-made reservoir that measures a circumference of 1,200 feet and was likely used as a bathing pond for visitors entering the monastery. Greenery fills the reservoir today, which is lined with large stone steps and once held an estimated 2 million gallons of water. A path on the southern bank of the Banda Pokuna crosses a stream and leads to the monastery’s entrance along a stone walkway.

The stone walkway is one of Ritigala’s defining features and a testament to the craftsmanship of ancient times. Image courtesy writer

Roughly halfway along the walkway is one of three ‘roundabouts’. It is around here that a path leads to sunken courtyards, which once housed buildings belonging to the monastery. The nearest structure is referred to as Padhanaghara Pirivenas or ‘double-platforms’. These structures consist of two raised platforms formed by retaining stone walls that are oriented east-west. The eastern platform is rectangular, open, and without column bases, while the western platform is square, smaller, and features column bases that suggest a roof housing several rooms. The double platforms are linked by a stone bridge and surrounded by a small moat, which is believed to have provided natural air-conditioning when filled with water. Furthermore, the open platform suggests the practice of communal meditation while the other suggests meditation in private.

Padhanaghara Pirivenas or ‘double platforms’ are characteristic of Pansukulika monasteries. Image courtesy writer

To the right of the first pair of double platforms is the site of the monastery’s ayurvedic hospital. Remnants of tools still remain, along with large stone-cut baths where individuals would be immersed in ayurvedic oils. One of the most striking features of the ancient hospital, however, is the urinal stone, which seems to be the only decorated ruin found in forest monasteries. In the Handbook For The Ceylon Traveller, W. R. McAlpine and David Robson say:

The most plausible hypothesis suggests that they represent the architectural and ritualistic excesses of the orthodox monastic chapters to which the Pansukulikas were opposed, and the act of urination was for them a symbolic act of dissociation.

The urinal stone is the only decorated ruin found in forest monasteries. Image courtesy tripinshorts.files.wordpress.com

Mountains Of History

The Riti trees (Antiaris toxicaria) found on the middle slopes of the forest are commonly believed to have lent Ritigala its name. However, when Bell surveyed the area on his 19th-century expedition, he discovered two boulders that included an inscription of ‘arittha’—a reference to ‘Aritthapabbata’, the name given to Ritigala in Sri Lanka’s ancient chronicle of the Mahavamsa.

While ‘pabbata’ means ‘mountain’, ‘arittha’ is a Pali word with two meanings. The first— ‘dreaded’—refers to the indigenous Yakka tribes that once resided at Ritigala. Clouds and mist shroud the peak for most of the year, giving its microclimate more rainfall than the surrounding dry zone at the foot of the mountain. As an SNR, this vegetation is now protected by law. But McAlpine and Robson note that similar rules may have applied when the mountain served as a historical abode of the Yakkas. They mention a legend which went that “whoever violates their ancient injunction of removing no part of the vegetation from the mountain will be punished by the guardian-spirits”.

Clouds and mist shroud the peak for most of the year. Image courtesy amazinglanka.com

The alternative and perhaps more historically relevant meaning of ‘arittha’ is ‘safety’. The Mahavamsa recounts the fact that Prince Pandukabhaya took refuge at Ritigala, where he hid from his eight uncles for seven years in the 4th century BC. Pandukabhaya then amassed an army with the help of the resident Yakkas, slew his uncles, and marched on to establish the royal city of Anuradhapura. In the 1st century BC, King Dutugemunu camped at Ritigala before defeating the Chola king, Elara. Later in the 7th century AD, King Jetthatissa sought refuge in a similar manner to Pandukabhaya, before ascending the throne in Anuradhapura. Ritigala’s reputation as a safe haven continued into modern history when insurgents made it a stronghold in 1971. However, their battle was not as victorious, and they were eventually flushed out by the army.

Shrouded In Mist And Myth

Stories of battles fought at Ritigala have also found their way to folklore. One story recounts a duel between two giants—a warrior called Jayasena from Ritigala, and another giant named Gotaimbara, who is likely to have been one of King Dutugemunu’s giant warriors. Jayasena was decapitated during the battle, at which point the deity Senasura placed the head of a bear upon his torso, thus giving life to the local demon Maha Sona.

Over the course of history, Ritigala and its beautiful surrounding areas have seen plenty of conflict. Image courtesy wikimedia.org

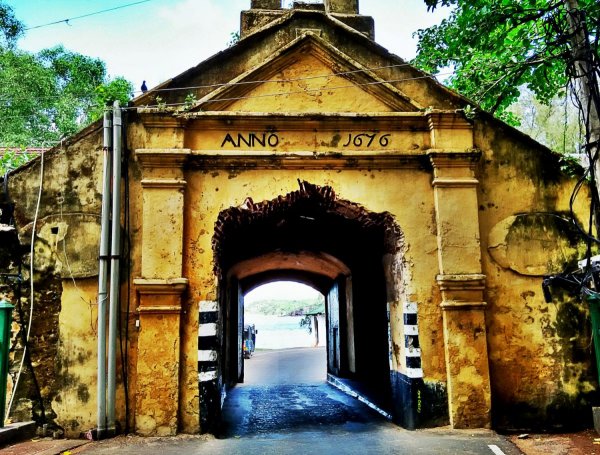

Ritigala is also mentioned twice in the ancient Hindu epic of the Ramayana. First, when the monkey-god Hanuman used the mountain as a launch pad to leap back to South India after discovering where Ravana was holding Sita captive. Second, when Hanuman was sent to the Himalayas for the medicinal herb Sansevi to heal Lakshman (Rama’s brother) at war in Sri Lanka. Having forgotten which herb was required, Hanuman returned with an entire chunk of the mountain instead. On his way back, three pieces of this chunk are believed to have fallen around Sri Lanka. One of these spots is believed to be the summit of Ritigala, complete with contrasting microclimates and species of flora found nowhere else in the world.

Legend has it that the monkey-god warrior Hanuman dropped five pieces of the Himalayas in Sri Lanka – one of which is the summit of Ritigala. Image courtesy amoghayan.files.wordpress.com

Rare Species Of Flora

Beyond its mythical connections, The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has described Ritigala as ‘a refugium for many rare and threatened species of plants’. As the world’s largest environmental network, the IUCN serves as the global authority on the natural world and is dedicated to its conservation through reputed expertise.

According to a case study published by the International Institute for Environment and Development, the ecosphere of the SNR hosts 417 plants. Of these, 337 are flowering plants (of which 57 are endemic to Sri Lanka), and three are endemic to Ritigala’s distinctive biome.

Conservation For The Future

In addition to the rare species of flora, the Ritigala SNR also boasts high biodiversity, which requires stronger conservation efforts.

A 2008 Biodiversity Baseline Survey notes a proposal to establish the Yan Oya National Park on the eastern boundaries of Ritigala. The park would serve as one of two corridors for elephants migrating between Kaudulla National Park and the Kahalle-Pallekelle Sanctuary—an area near the Hurulu Forest Reserve, where a suggested corridor linking Ritigala was also cited by the IUCN in 1990.

Ritigala could be Sri Lanka’s ninth UNESCO World Heritage Site. Image credit: Flickr/VSL Travels

Proper conservation efforts focused on its cultural and natural heritage could make Ritigala a potential contender for a ninth UNESCO World Heritage Site in Sri Lanka. The UNESCO website states that “To be included on the World Heritage List, sites must be of outstanding universal value and meet at least one out of ten selection criteria.” Ritigala seems to satisfy most of these at first glance.

An article last month quoted Education Minister Akila Viraj Kariyawasam (under whom the Department of Archaeology falls) as saying that UNESCO has warned the Sri Lankan Government that several World Heritage Sites may be de-listed due to poor maintenance, citing unlawful settlements as the primary shortcoming. While this is cause for alarm, Ritigala still holds an advantage as an SNR, since human settlements are prohibited. Although the area has a significant amount of cultural importance, Ritigala has the potential to become popular as a Natural World Heritage Site.

Visiting Ritigala

Ritigala is located in the North Central Province, less than 200 km away from Colombo, and can be easily accessed from the main hotspots within the Cultural Triangle such as Anuradhapura, Dambulla, Habarana, Polonnaruwa, and Sigiriya. The best time to visit is early morning, not only to escape any crowds but also to enjoy the serenity of the monastic ruins that make Ritigala a must-visit destination for any traveller.

Featured image credit: nirvairrai.wordpress.com