in Dhaka. Photo: Mabruk Kabir/World Bank

On a foggy winter morning in Dhaka, 41-year-old Jahid was sipping tea by a roadside stall.

“Life was very peaceful back in my village,” he reminisced, “but there was no work, so I moved to Dhaka. Even if I live in a slum, my children are better off here.”

Jahid is one of the 500,000 people that move to Dhaka city each year. Driven by the promise of economic opportunity as well as poverty in rural and coastal areas, it is estimated that half the population of Bangladesh will migrate to urban areas by 2030.

Urbanization can be catalyst for growth. Density – the clustering of firms and workers – can drive productivity, innovation and job creation. It is the benefits of agglomeration that once drew the country’s most important industry – the ready-made garments sector to Dhaka city.

However, it is the costs from congestion that are now pushing factories away, mainly to peri-urban areas. Why are factory owners leaving?

For starters, the tide of new migrants has overwhelmed urban infrastructure, basic services, as well as the stock of affordable housing – eroding the both the livability and competitiveness of Dhaka city. A recent World Bank report described South Asia’s urbanization trajectory as “messy and hidden” – reflected in the large-scale proliferation of slums and urban sprawl.

The Slum Effect

With the rapid influx of new migrants, the demand for land and housing has skyrocketed in Dhaka, pricing many low- and middle-income households out of the formal housing market. Unaffordable housing has pushed millions into slum and squatter settlements. Consider this: in Bangladesh, 62 percent of the urban population lived in slums in 2010.

Slums are poverty traps. While 55 percent of urban slum households are poor—a share larger than in rural areas – 23 percent of slum occupants live in extreme poverty. There is compelling evidence that slum-related factors make it particularly difficult for households to climb out of poverty. The average slum household has a harder time accessing finance, finds it more difficult to commute to work, and has poor access to basic services – including schooling for their children.

When asked, Jahid admitted that his sons had not enrolled in school. “They have to work ,” he explained.

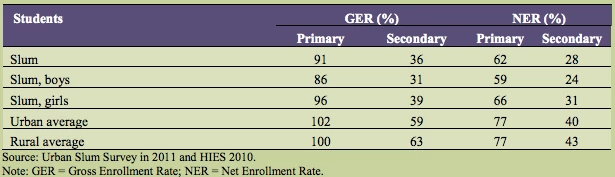

Falling through the CracksJust how large is the education gap in slums? For starters, metropolitan areas with large slum populations fall behind rural areas in terms of school enrollment. The overall gross enrollment ratio (GER) in slums is 10 percent lower than the nationwide average, for instance, while the net enrollment ratio (NER) is 15 percent lower. Even within same municipal area, children in slums are less likely to enroll in school, and more likely to drop out than children just outside the slum.

Poverty is a key factor. Between the poor and the non-poor living in slums, there is a gap of 18 percentage points in the gross enrollment rate. The gap becomes more pronounced - 24 percentage points - as we move to up to secondary education.

The low education attainment of family members is another impediment to enrollment. Only 58 percent of slum inhabitants over the age of 12 are literate, compared to the overall urban literacy rate of 72 percent.

When children don’t go to school, they don’t acquire basic literacy and numeracy skills. In a survey of out-of-school slum children in Dhaka, a learning assessment found that about half the children were not able to write their own names correctly. Only a quarter of children could read a short passage independently. Numeracy skills were equally concerming - about 37 percent could recognize two- digit numbers, and 6 percent of children could perform simple arithmetic. Like enrollment, learning outcomes were worse when the household head was not educated, or when children came from poorer households.

Bangladesh is in the midst of economic transformation. As more migrants move to urban areas every day, policy makers have to ensure cities are able to connect to markets and deliver services to its residents. But productivity and innovation also require a healthy and educated workforce. If the country is to achieve middle-income status, will also need to invest in the skills of its youth – ensuring all its children have access to quality education, especially the ones hardest to reach.

Join the Conversation