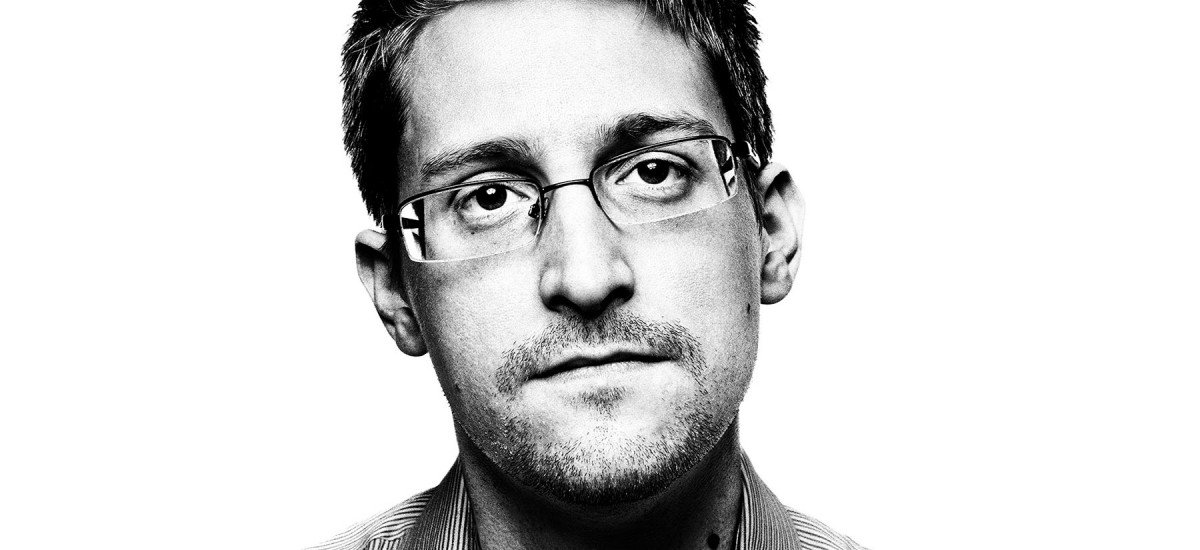

On Tuesday last week (12th) I watched, at the Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute the screening of ‘Citizen Four’: A documentary film concerning systems analyst Edward Snowden and the information he leaked on the nature and scale of the NSA’s spying activities. In that documentary, director Laura Poitras records the manner in which she was first contacted by Snowdon via encrypted email messages and her subsequent dealings with him, holed in a hotel room in Hong Kong, together with Guardian journalist Glen Greenwald who ‘broke’ the story and Ewan MacAskill.

In one of the more memorable scenes in the documentary, the affable, soft-spoken and intellectual Snowdon while sitting on the bed, asks Glen, sitting on a chair across from him, to pass him his ‘magic mantle of power’ – a red blanket with which to conceal himself while encrypting Greenwald’s email. When handing him the blanket, Glen asks – “Is that about the possibility of overhead?” to which Snowdon replies, “Visual. Yes. Visual collection,” – indicating not just the NSA’s ability to extract visual data but also his fear that they would. Greenwald’s reaction to Snowdon’s affirmation was – “I don’t think at this point there is anything in this regards that would shock us”, and then, referring to Ewan – “Ewan was like, I’m never leaving my room, I’m never leaving anything in my room again.” And then I was like (laughing) “You’ve been infected by the paranoia bug, happens to all of us.”

It was this paranoia I found the most interesting.

It was sometime in April 2013, that I wrote my last blog post. Titled ‘And Then They Came For Us’, or something along those morbid lines, the piece was a commentary of sorts based on tweets, photographs and Facebook updates sent out by friends attending a peaceful vigil at the center of Colombo, when marauding thu monks disrupted their activity. In the aftermath, as a mini-war broke out online with images of participants shared at a furious rate by the disruptors, accompanied with vicious, inflammatory and inciteful comments, I began the quiet job of dismantling my blog and cleaning out my ‘online footprint’. It was not just that I was disturbed at the way hate spewed forth online; the Government’s increasing interest in the world of the wide web had me convinced it was a matter of time before public example would be made of online activists.

It was not as though events of that nature were unprecedented: In Tunisia, Egypt, Russia and Syria bloggers had been arrested by their governments for a variety of crimes – the intention to make public example of, and in that they succeeded. In Sri Lanka, when on the heels of a raid on the offices of Lanka Mirror, Lanka X News and arrest of 9 of its employees the Government announced its intention to amend the Press Council Law to bring any website containing news on Sri Lanka under its purview, pundits believed intention to be darker that what was led to be believed: The move was not to protect against the publication of spurious or defamatory information, but rather, to gain control over a thriving online hub for ideas and communication.

In the months that followed, rumours of Chinese complicity with the Government swilled: The whispered information that a Chinese team had arrived to aid the Government with online surveillance was not hard to believe, given the context; the Former President Mahinda Rajapaksa had shown reciprocal preference for China over India, the United States and other traditional allies. China by nature is picky about democracy, preferring to dish on communism instead, and is, to quote the Human Rights Watch 2014 World Report: ‘an authoritarian one-party state…places arbitrary curbs on expression, association, assembly and religion; prohibits independent labor unions and human rights organizations; and maintains Party control over all judicial institutions. The government censors the press, the internet, print publications, and academic research, and justifies human rights abuses as necessary to preserve “social stability.”’ In effect, China is a world unto itself, to add to which it has developed its own platforms for online communication, severing her people from communicating with the rest of the world.

The Government took on a media presence – Former President Mahinda Rajapaksa hired a crack team to handle his social media and enlarged that presence on Facebook and Twitter. The Former President’s son MP Namal Rajapaksa and his siblings also began communicating with the world, by and large, using these social networks. The entrance of these players to what William Gibson in 1982 termed ‘cyberspace’ greatly changed the nature of communication on the topic of the state and its organization; where before there had existed the freedom of expression, now crept in the heavy hand of self-censorship from which mainstream media and the ‘offline’ world had suffered. The gradual awareness that the integrity of major service providers had been compromised came when the more news-centric of consumers realized it was no longer possible to access The Colombo Telegraph, an online news publication that sprang into existence during a time of severe media repression. The Colombo Telegraph, a ‘public interest website relating to Sri Lankan matters, run by a group of exiled journalists,’ lists, among its missions and objectives, the need to reverse self-censorship: ‘there is perpetrated on the media a psychology of fear through abductions, killings and other forms of pressure…This needs to be stopped.’

Making example of through abductions, killing and other forms of pressure had been a modus operandi successfully employed by the government previous. It was Frederica Janz, one of those in the last line of defense, who said of the previous government, it waged two successful wars – one against the rebel LTTE faction, the other against the media. Her predecessor Lasantha Wickrematunga we know, was gunned down – his murder unresolved to date. The whereabouts of Prageeth Eknaligoda – if indeed he still counts among the living – remain unknown. At the last stages, as the Chief Justice Shirani Bandaranayake was escorted out the hallowed halls of justice by means of a controversial, illegal impeachment; as Mandana Abeywickrema’s home broken into, her family held hostage; and circulars denying non-governmental organizations funds from outside the country issued, Sri Lanka slipped from deep into deeper dire straits.

In the years that followed the removal of all traces of my activism and anti-government sentiment from off the Internet, (and it has been about two), I have often wondered if it were paranoia that led me offline. But if it were that fear, it was not unfounded – it was together with awareness of the previous Government’s growing authoritarianism over both the online and offline worlds. I knew that if major service providers were made to, in the words of Dialog CEO Hans Wijayasuriya, ‘be complaint’ with Government requests, the likelihood of gathering metadata on citizens was very high, to say the least. I was just another young journalist, just another citizen activist, but watching as the people I admired went down, or struggled to gain ground; when my former Editor Frederica was forced, after long years of battle, to leave the country with her two sons, when my one time Deputy Editor Mandana’s house was broken into, and her daughter – the same age my son – held hostage, as whispered, fearful conversation increased and it became practice to remove the battery from of a phone to conduct conversation on the state, as email accounts were hacked into and privacy compromised, I knew it was time to retreat into the woodwork.

Journalists, the Judiciary, Activist, Academics and Politicians – these were the last line of defense before the Rajapaksa’s, and they were all, systematically, taken out in their own fashion. The ordinary citizen, the general populace uninvolved with matters of the state, had long since gone silent. Where it had been easy before to strike a general conversation on the cost of living or on the general state of governance, I found increasing resistance; people no longer wanted to talk – people were afraid to talk, even among themselves. The general populace – even if unaware of the nature of spying, how it was possible, how their privacy and the contracts drawn between themselves and service providers has been compromised and that trust betrayed, or how the covenant between the state and her people had been broken – knew, instinctively, to be quiet. Sanjana Hattotuwa, at the panel discussion at the screening of Citizen Four, called to attention the panopticon – a Bentham designed architectural device of the 18th century, which subtly encouraged its inmates to regulate their own behavior for fear of being watched.

“…The major effect of the Panopticon” wrote French philosopher Michel Foucault of Bentham’s work in Discipline and Punish: The Birth of The Prison, was to “…induce in the inmate a state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automatic functioning of power…to arrange things that the surveillance is permanent in its effects, even if it is discontinuous in its action; that the perfection of power should tend to render its actual exercise unnecessary.”

The fear of being watched, the fear of being made example of, the fear of being abducted in ‘white vans’, ‘disappeared’ or killed increased in the minds of Sri Lankans during the dark period we passed out of in the wee hours of the 9th morning of January 2015. It was a fear that began in the hearts of citizens stranded at the Nandikadal lagoon at the culmination of the civil war, and spread across the island the six years since, as one family’s desire to stay in power begat a systematic undermining of democratic processes. It was only when the miracle of a surprise candidate, newly deflected from the flank of the former President himself, won the majority vote of the people of Sri Lanka, that an end to the Rajapaksa’s corruption and abuse came. In the four months since the Presidential Election of January 2015, significant change has taken place – the most important of which, it is agreed, is the passage of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution. But I will argue, that the people of Sri Lanka are yet to recover from the trauma of the recent past – the pall of silence hangs still over the country. Evoking Niemöller as I had in the last blog post I wrote, recalling what advice Lasantha Wickrematunga gave freely from beyond the grave, I say this, if there is a lesson to be learned from the years under the rule of the Rajapaksa’s it is that we must not wait until they come for us – we must, with one voice, speak when they come after the journalists, speak when the come after the judiciary, speak when they come after the academics, speak when they come after the activists, and when those to whom you have given power abuse it, speak louder still.