It is an uncomfortable question – but one that tackles a stubborn social issue in Pakistan. In a country of 180 million, a culture of bribery and pretty corruption plagues public service delivery.

When visiting a land services official, a staggering 75 percent of households reported paying a bribe, according to Transparency International. Over half of households said they bribed the public utilities or a police officer in the last year. Endemic corruption is not just a drag on economic activity and poverty reduction efforts – it erodes trust between citizens and the state.

A new initiative is now attempting to rebuild that trust.

Zubair Bhatti, a senior public sector specialist at the World Bank, found that most petty extortion went unreported when he was a civil servant in Jhang, a district of Punjab. “People were not using the complaint cells at government offices,” said Bhatti, “It was often not worth their time. So instead of waiting for citizens to approach us with a complaint, we began calling them proactively for feedback.”

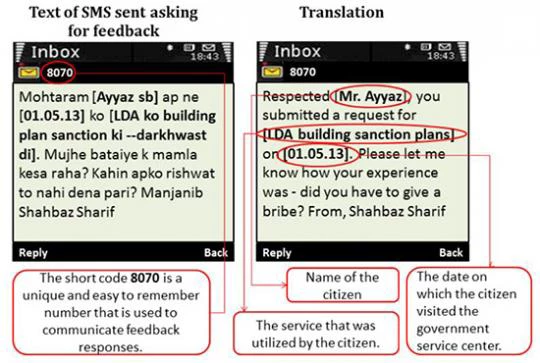

The initiative is now known as the “Citizen Feedback Model”, and is being scaled up across Punjab with support from the WBI Innovation Fund and DFID Sub-National Governance Program. When residents need a public service – whether that means getting a driver’s license, registering property or using public health services – they visit a local government office, which records the details of the transaction. This information is relayed to a call center, which reaches out to service users directly to ask about their experience.

While many receive direct phone calls, most receive an automated message – the Chief Minister’s customized “robo-call” – which allows the system to reach a much larger number of beneficiaries. The call explains that a text message will ask the recipient to take a survey to improve the service, and identify instances of corruption. In areas of low literacy, the robo-call gives the recipient a chance to seek help if they cannot read the text message.

So far, some 3.5 million citizens have been contacted, with over 15,000 cases of corruption reported.

Social Contract 2.0

Information technology can be a powerful tool to empower the citizen. In Pakistan, where mobile phone penetration is almost 70 percent, it is possible to reach even the poorest households. Not only can more individuals now hold their local officials to account, but more citizens have a direct say in the quality of government services – a key ingredient in poverty alleviation efforts.

“In addition to the obvious benefits to the citizen, there are large political dividends for the government as well,” noted Bhatti “Most Pakistanis are quite pleased to see the government reaching out and demonstrating concern for the common man.” In a country where 48 percent believe the government is captured by the elite, measures like the CFM can go a long way to rebuild trust. An accountable government is often perceived as more legitimate, and an efficient civil service is more likely to enjoy popular support.

While useful for exposing individual cases of corruption, the model can also be used to improve public accountability at the macro level. By collecting feedback in real time, “big-data” can be used to track patterns of poor service delivery – which can be used to draw geographic “heat maps” of bottlenecks in the system. This can be a powerful tool to disrupt patronage networks, which skew access to services based on political affiliation.

“The province of Punjab, led by an active ICT arm, is actively experimenting with ideas so that the government and citizens can collaborate,” Bhatti notes. From containing dengue epidemics, to tracking absenteeism among public teachers and doctors, ICT is breaking the monopoly of information held by local government officials – and in the process, improving public performance and service delivery.

Of course, technology is no silver bullet. ICT merely amplifies existing citizen engagement. A new generation of governments must embrace an ethos of open and inclusive governance, or risk falling behind. Across the board, the contours of a new social contract is emerging, one where citizens seek a relationship with their governments based on transparency, accountability and participation. The government of Punjab is responding, in this case one text message at a time.

Related Resources:

Feature: Leveraging Mobile Phones for Innovative Governance Solutions

Blog: M-government, Innovations from Punjab

Press Release: World Bank to Support Punjab in Delivering Quick Results

Project Documents

Join the Conversation